- Home

- Andrzej Bursa

Killing Auntie Page 5

Killing Auntie Read online

Page 5

“Why do they take you for a relic thief?” I asked.

“Ah, this …” he smiled. “ I stole a golden arm.”

“From the Capuchin church? I know this golden arm well.”

“From the tone of your voice, sir, I conclude that you have lived in the New Town for a time and are familiar with the magic of the golden arm. I was troubled by it too, and more painfully than you, and for much longer. I’m twice your age. I’m forty-seven years old, nearly fifty.”

“The golden arm was, if I’m correct, given to the abbey in the seventeenth century.”

“Sixteenth. Your error is actually perfectly excusable, for it happened at the beginning of the Baroque period. In 1598 to be precise. Kazimierz Hermanowicz joined the order and the arm was kept in the abbey’s treasury. Only after his death in 1610 was it put on public display, thus fixing the conviction that the arm was in fact given to the order in the seventeenth century.”

“Do you know other details connected with Hermanowicz?”

“Oh yes. The question of the golden arm has interested me for a long time. The moment I heard God’s voice telling me to steal it, I began to study the matter in earnest.”

“Did you hear God’s voice?”

“Huh, let’s not simplify this …”

I didn’t hear the rest of the relic thief ’s answer. The drunks, after a rest, burst out with their madness again. One of them snatched the other’s belt with his teeth and now both were chewing on it, growling and tugging at it, each to himself. This tug of war went on for a while until an apocalyptic roar communicated to us that one of the drunks had lost his tooth. The thrashing on the floor stopped. Out came sobbing and words of succor. At last the two bodies rose and began to urinate in silence against the opposite wall.

“You were asking,” resumed my interlocutor, “if I heard the voice of God. I think we should not pose the question this way. I am not one for spewing revelations. God’s will speaks to us without any metaphysical packaging. It simply manifests itself through certain decisions and thoughts in our brain. Through a certain order of events in our lives. I, my dear sir, have been dealing in sacrilegious thieving for a long time now. But they were mostly trifles.”

“Trifles?”

“Yes. Do you remember that little cherub with a porcelain head, nodding thanks every time someone put a coin in the box? He was my benefactor for two years. Every week I knelt before the box, sunk in prayer, during which I would pick the lock with a needle and take out the coins. I was caught by accident, in a silly way, as usual. Later I was involved in other sacrilegious thefts. Small votive candles, and once I had a go at a chalice. But a serious matter like the golden arm I hadn’t tried before. It’s a difficult case. It’s possible I will rot for the rest of my life in jail.”

“Couldn’t you try a psychiatrist?” I was worried I may have offended the sacrilegious thief but he showed no sign of taking offense.

“It’s my only hope,” he replied gently, “but whether it’s going to be successful this time remains to be seen. It’s already helped me once, when I was put on trial for the chalice. I shammed it rather badly and they didn’t believe me. Only when I started explaining the true philosophical motivation behind my actions did the doctor write out a certificate that saved me from five years in prison. I think now I have to take a similar route. Tell the truth. Truth opens the gates of heaven. It’s interesting how many people claim to be following the teachings of Christ yet practically no one understands their true sense. So far it’s served me well. They take me for a madman. And yet it’s so childishly simple, like the sunshine. Since God created the sacred, he had to create the sacrilegious. Since at the root of our religion lies the legend about a murder, it’s natural that murderers have to exist. You killed a man …”

I shuddered. The sacrilegious thief didn’t notice and continued:

“In your case, the primitive desire of enriching oneself or exacting revenge …”

“I didn’t kill to enrich myself, or out of revenge,” I interrupted him.

“Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to pry into your personal affairs,” the sacrilegious thief apologized politely.

I said in an unnaturally high voice:

“I simply killed.”

“That’s OK too, young man,” my companion smiled gently, and then asked:

“Are you a believer? Please excuse the forthrightness of my question.”

“No.”

“I thought so. The youth of today is mostly unbelieving. Without unbelievers the church would not exist. But I do hope one day you will find your path to God.”

“It’s very kind of you to wish me well,” I replied politely. “Trouble is, I have very little time left to find that path …”

“Hm, true,” smiled the sacrilegious thief. “But let us be of good faith.”

My conversation with this kind man absorbed me to such an extent that I didn’t hear the steps in the corridor. When, pulled roughly by my sleeve, I was leaving the cell, my companion didn’t even send me a parting look. In the other corner the two drunks were snoring away, soaked in urine and blood.

“Student … Yes … Very well … Which college?”

I gave the name of my university. The desk sergeant looked at me sternly and disapprovingly. The policeman standing next to him smiled.

“A learned man,” he opined spitefully.

I was very ashamed. I stood humbly in my socks, holding up my falling trousers. They still had my shoes and belt. There came a moment of weighty, contemptuous silence. I smiled differentially.

“Citizen Officer,” I said, “Saturday. It happens …” and opened my arms in a gesture of hopelessness.

The duty officer liked it. He didn’t smile, but in his eyes there flickered a brief, humorous spark. He frowned and asked:

“How much did you shell out yesterday?”

“I wasn’t paying.”

“Hm …” The duty officer began to leaf through the papers and engaged in a conversation with the policeman. It went on for ages.

I used every moment they turned their heads to arrange my face into a sneering grimace. Apart from the three of us there was also a young lady in a scarlet fur. She had come to the station to ask about her fiancé, a petty thief with whom she had spent the night. The woman was richly rouged, pretty and full of scorn. Her presence embarrassed me greatly. I felt deep shame in her presence, what with my dishevelment and the whole jail situation. She wasn’t looking at me at all, which hurt even more. At long last the duty officer finished his conversation, rose from his chair, put his hands in his pockets and began pacing the room. He stopped at the window and looked through the windowpanes with calm concentration. Then he came up to the locker and took out my student card, my belt and the shoes.

“Get dressed,” he said. “I hope I won’t see you here again.”

I wished that more fervently than he could ever guess.

6

THE RELIEF WHICH FILLED ME TO THE BRIM AFTER LEAVING the police station, at home turned into depression. Sitting on the bed I ruminated on my merciless fate, which kept throwing me higgledy-piggledy into cruel, humiliating adventures. The thought that I had just brushed against the gallows, in fact slipped through the noose, didn’t give me any satisfaction. I had made a fool of myself. Cringing and cursing myself, I recalled the details of the past night. The memory of my drunken exploits at Jacek’s pressed so heavily on my mind that even though I was already lying in a half-slumber, I extricated myself from the bedsheets and snatched my coat.

With pitiless stubbornness I played back the infamous episodes, my childishness, my stupidity and my fall. And then, suddenly, came the fear. I knew fear well. It had come to me several times in the last few days, with greater or lesser force. The new attack was dangerous. I recalled with terrifying clarity how I’d screamed at Jacek’s, “I’m a murderer!,” how I drank, how I kept saying in the street, “Now I’ll cut her head off!” moments before being stopped by the po

lice.

It was six in the morning. The hangman’s hour. Shaking with cold and terror I lay fully dressed on the bed and pulled the sheets over my head. But the calm wasn’t coming. I leaped out of bed and with all my strength started slapping my face. In spite of my faint, frozen body I threw off my jacket, sweater and shirt, and began to exercise vigorously. I tortured myself with sit-ups, push-ups and handstands, listening to my pounding heart and wheezing breath. I ran to the bathroom and put my head under the tap, then began massaging myself with karate chops and kneading my muscles until I was in pain. Then I got dressed and went back to the kitchen. I put the kettle on the stove and made myself a cup of hot tea.

Gritting my teeth and determined, I returned to the bathroom. The saw and the axe were already there. The fear had left me, as always when I focused on a concrete job. I pulled the sheet off the corpse. Rolled my sleeves up. And began to saw the other leg. I used the tried-and-tested method. First the foot, then the calf.

Shrrt-shrrt … shrrt-shrrt … shrrt-shrrt …

When I’d shortened the second leg just like the first one, I had a break. I allowed myself a cigarette. It was tasteless. I went back to work. With a few short blows of the axe I crushed both knees. I turned the top of the toilet seat into a workbench where I laid out the axe, saw and an open penknife. Taking turns with these tools I managed to disconnect the stumps from the rest of the body. Now the corpse lay comfortably in the bath. It occurred to me that I had made a terrible mistake in not bleeding the corpse while it was still warm. I would have had a much easier job. But it was too late for regrets. With the penknife I cut through the dress on the torso and peeled it off bit by bit. Without disturbing the corpse I managed to bare it completely. I rolled the rags into a ball and stuffed it behind the kitchen stove.

That was all I could do with the corpse in this position. To proceed with severing the remaining limbs the corpse had to be repositioned. I thought about it for a while, then grabbed it under the arms and lifted it. The effort was killing me. Soon I felt hammers banging on my temples. The corpse began to put up resistance again. The lolling head just would not rest on the rim of the bath. I wasn’t giving up, though. With all my muscles strained to the limit, I pulled the corpse up over the bathtub’s edge. I gave it another pull and when the resting point came to about halfway down the back, it finally kept its balance. I began to saw. I was trying to steer the saw away from the ribs so it cut only through the flesh. When I reached the spine my arms were numb and black wispy blotches floated before my eyes. But I didn’t want to stop the work halfway through. I sawed on. The body began to quiver and tilt. I mobilized all my energies to keep it steady. At last the spine gave in. From then on it was all a breeze. I pushed the cut-up remains back into the bath.

The corpse ceased to be a whole. It lost its corporeal identity. Inside the bath lay the stomach and thighs, flanked by the breastbone on the one end and knees on the other; on the tile floor – an oddly proportioned bust with two large breasts, a head and very long arms. I picked it up by the hands and threw this … shape into the bath. Then I covered the flesh with a sheet. For it was flesh. Just flesh, not a corpse. Not even a carcass. My victory over the corpse was therefore a victory only over form. The body was still in the bath and not a tiniest piece of it had been annihilated. It was, if anything, a moral victory. More like capturing of the enemy flag. The corpse had lost its flag.

The third day of my battle with the corpse was coming to an end. It should start decomposing now. In some warehouse I bought several pounds of crushed ice and laid it over the remains. Over the bathtub, I put down three small planks and placed a few of Auntie’s plants on them. In the center, Auntie’s collection of cacti, on the sides, a tiny papyrus and an araucaria. The bathroom acquired a very pleasant ambience. Something like a tranquil little chapel.

The following day I took one of the remains out from under the sheet. At first I couldn’t work out which part of the body it was. That pleased me. I wrapped it carefully in paper and tied it with a string. On the parcel I wrote an address. I had been thinking about this address for hours, rejecting the more eccentric ideas so as not to make it look too suspicious but trying to avoid banality or unwarranted carelessness. I opted for a surname ending in the rather normal “-ski,” but with a combination of preceding letters that was unusual and beautifully sonorous. I added some class to the popular name of Edward too by spelling it with a v. And gave the sender the witty and laconic name of Antoni Nul.

The clerk at the post office cast a critical eye over my parcel.

“What’s in it?” he asked.

“Perishables,” I explained.

“Write that down. Besides, it’s not tied properly. There … see?” he shook the parcel and the strings began to loosen up and slip off.

I struggled contritely with the string for a long time, then timidly asked for a bit of sealing wax, with which, in all that confusion, I burned my fingers. At last the parcel was accepted.

After my lectures I bought a larger amount of string, cardboard boxes and paper. I prepared two types of ink, a pen and a pencil. I spread out a plan of the town and a map on the table. I scoured the plan in search of streets with amusing or lyrical names and wrote them down. To my fictional addressees I gave names of characters from my favorite books. I had to give those names Polish forms, which was a lot of fun. I wrote alternately with the pen and the pencil, and changed the ink. From time to time I also changed the style of writing, now making it look like the clumsy scrawls of an illiterate, at other times drawing straight lines in pencil. I remembered that among Auntie’s few books was a manual of calligraphy. The old, little book, after years of neglect, was to be useful again. I studiously practiced the old-fashioned flourishes, ruining three sheets of paper in the process, until I achieved a perfect example of the old style. As the hours passed I grew calmer and hopeful. After filling those fifteen boxes and sending them out, I would proclaim victory.

At long last all the addresses were ready. I brought a piece of the body from the bathroom and started wrapping it up. Suddenly I stopped. I was overcome by a wave of fatigue. And with it – fear. I was familiar with this condition. Whenever I got absorbed in some light task – heavy manual labor was out of the question – after some time I began to feel a rising anxiety. It was a vague sense of terror, dejection and depression, which had only been temporarily tricked by my activity. Today, the anxiety was more tangible and easier to overcome. If before I was simply unable to find a logical explanation of why I was engaged in reading a particular book or puzzling out a certain test, now finding a justification for my action was straightforward and irresistible. The battle with the corpse had liberated me from those unmanly histrionics and feebleness. It was the first difficult and dangerous task I had ever faced. Although the panic attacks still happened, they had a real cause. I learned to overcome them through cold rationalization of my current situation, from which followed the choice of appropriate actions. This time, though, the fear seemed to be better grounded than usual. For as soon as someone would unpack my parcel in some remote little town, another person somewhere else would pin a little flag on the dot denoting our town on his map. The more parcels bearing stamps of my local post office that were opened in various corners of the country, the more leads for our policemen to conclude that the murder took place here rather than anywhere else. At the same time, I was aware that the day I should inform the authorities of Auntie’s disappearance was getting inexorably near. The date I’d give them would have to coincide with the time of death, which would be established by forensic analysis of the remains. And that would be suspicious, for sure.

It was possible – I reasoned with myself – that my thinking was full of holes due to my lack of experience. Nevertheless it was undeniable that by sending the remains by post I was giving the detectives a certain advantage. I was disappointed. All that nice, calming work would be a waste of time. There was nothing to do but to tear up all the fictitious addresses, t

he inventing of which had been such a pleasant distraction; pleasant not only because it was fun but also because I believed it to be useful. Once again it crossed my mind that the annihilation of the corpse was harder than might be generally believed, that the struggle was tough and the adversary brave. So – what to do? I thought of the river. I had already been to check it out. The banks were frozen, so a parcel would have to be thrown in away from the ice. But I wouldn’t dare to drop it from the bridge, even in the middle of the night. Unless I packed it all away in a sack … A sack, I needed to buy a sack. Come on – I was getting annoyed with myself – where does one buy a sack? I went in my mind through all the shops I knew, yet I could not remember a single one where they might be selling sacks. I gave up. I was sure I’d find one. But then, who needs a sack? I’d take a few parcels and throw them into the river outside of town. I decided to go there the next day. Confidently, I wrapped the piece lying on the table and put it in the box. Then started slowly tearing up the labels with fictitious addresses.

Still, the moment I tore up the first paper, the doubts returned. I took the parcel out to the bathroom and stretched myself out on the bed. My experience with the corpse had taught me to avoid harried, unpremeditated actions. I thought that by giving the authorities the advantage in sending the parcels by post I could immediately turn this advantage … to my advantage. OK, tomorrow morning, at an anonymous post office, my parcel would arrive bearing the postmark of our town. But what if another post office receives a parcel bearing a postmark of another town? And the day after tomorrow another parcel with another piece of the corpse would be stamped in another town altogether? Even if they eventually came to the conclusion that there’s one murderer, how would they decide his true address? Rather, they would assume that mailing the parcels from different towns was a deliberate ploy. How could they tell that the murderer would start with his hometown? Such a perfidious criminal would know to steer clear of any post office near his permanent address. Who knows, maybe it would be a dot without a flag that would come to be the focus of the investigation? I went on honing my plan. I rejected the idea of visiting several towns in a row. That would be too expensive. Moreover, what excuse would I give at the university for absenting myself from the lectures? Still, the advantage, once relinquished to the enemy, had to be immediately turned around. Tomorrow I would take three parcels and mail them from the main post office in a big town two hours away by train. That should be a big enough stick in the spokes of the investigation. The rest of the body I would dispose of here by different methods.

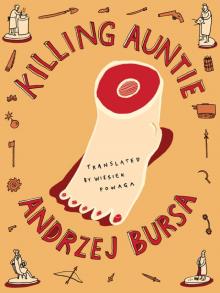

Killing Auntie

Killing Auntie