- Home

- Andrzej Bursa

Killing Auntie Page 6

Killing Auntie Read online

Page 6

From the pile of addresses on the table I picked out those that struck me as the funniest and returned to the packing. The overall weight of the parcels was one hundred and twenty pounds. I took them out to the bathroom and burned the papers with addresses.

7

TRAVELING HAD ALWAYS HELD A CERTAIN ATTRACTION FOR ME. In my modest experience I had traveled little and every trip, even the shortest one, was for me a source of amusement and an adventure. In a different town I felt a bit like a foreigner. It was still before midday when I had all the parcels posted and so I went for a stroll around the town. Luckily, it was warm and sunny. Mailing the parcels was a big step forward. Pleased with the progress, I decided to spend the rest of my time in town on small pleasures. When I got tired walking the streets I stepped into a café. I treated myself to a big coffee and two cakes. I had my lunch in a good restaurant, choosing the menu with the sedulous care of a gourmet. After lunch I felt a little tired. My return train was in the evening. Wandering around, I came across a cinema. They were showing a movie it was impossible to get tickets for in my town, but here I bought one without trouble.

Movies make me feel vulnerable and leaving a cinema is almost always a nasty shock. The exotic glamour of the strange town was shattered, showing all its fragility. The station was merely dirty and noisy. Many times I have promised myself to go to the cinema every day, to spend much of my time – I was afraid to say: life – in lethargy. I never fulfilled my promise.

The compartment was not overcrowded. Opposite me sat a girl, reading a book. She was pretty. I was observing her with pleasure, the light auburn lock of hair on her forehead, a small nose, her dark, resolute eyebrows. She had delicate, shapely hands. With sadness I thought that soon she would leave the compartment and I’d stay behind, alone with sleeping workers, or maybe she’d get off the train with me in our town, but then we’d lose each other in the crowd. I would be left alone. Almost with gratitude I thought about my corpse, the struggle with whom somehow filled my loneliness.

The train was moving at a sleepy pace. We were passing the scattered lights of villages and small towns. The lightbulb hanging from the ceiling gave faint, murky light. How can she read? – I thought about the girl. And without any premeditated plan, I said:

“You will damage your eyes.”

The girl quickly raised her head and frowned lightly. Then she smiled and put away her book.

“Thank you,” she smiled again. “I’m used to it, they always tell me off for reading in the dark.”

“And quite rightly too,” I replied solemnly.

We started to chat. At first I was afraid that our light, casual conversation would suddenly break off after some trivial remark, that after a few stops, before we reached our town we would fall silent, running out of things to say. But as we spoke the risk of that happening faded away. We slowly relaxed into our chat and the moments of silence that fell from time to time between sentences did not separate us. We were silent together. At some point I felt the girl’s hand on my knee. I appreciated the gesture but still didn’t dare touch her hand.

We were smoking cigarettes in the empty corridor. In a distance, far from the tracks, passed the lights of some settlement.

“When I was little,” said the girl, “I believed that those lights were elves’ lanterns. During the day the elves slept and no one knew about them. But at night they would come out onto the hills and light their lights. The oldest elf, their king, lit a red a lantern. Me and my brother were always looking for the red lantern of the king. Did you believe in elves?”

“Of course.”

“Your answer lacks conviction. I sense the irredeemable influence of a rationalistic upbringing.”

“But you are still very young.”

“Ah, you old men … I see you have acquired the arcane art of old-fashioned gallantry … Never mind, let’s look for the red elf.”

“So far we haven’t been very successful.”

“So what. The greater the effort, the sweeter the reward. O look, there … the green one. He is also an important elf. Though he is far below the red king.”

“I understand that the kingdom of elves has its own bureaucratic hierarchy. I wonder who is in charge of the elven field workers?”

“Boring realist. It’s clear you never believed in elves.”

“I assure you, I did, but …”

“But?”

“But I stopped. I simply grew up and started thinking seriously about the future.”

“Very commendable.”

“Very. And by the way, I’d gladly give a big part of my life – I don’t have any other capital – to someone who could convince me there is a future.”

“Hm, a Hamlet too.”

“Yes. A Hamlet. But unlike thousands of other native Hamlets, I have at my disposal a real skull.”

“Strongly put.”

“I’m sorry, I won’t bore you any more.” Suddenly my spirits flagged.

“Hey, what’s wrong …?”

“Nothing. Nothing worth talking about.”

“But why? We can talk. It’s high time …”

I smiled bashfully.

“I’m very pleased we met. I hope we’ll meet again.”

“Well, I’ll live in hope.”

We stood in silence. I was focused, filled with blossoming joy.

“It’s really great …” I mumbled after a while.

“What?”

“That I’ve found the red elf!” I cried out, pointing quickly at a red light glowing in the distance.

We both burst out laughing.

8

IT WAS A CLEAR, STARRY NIGHT. I WAS RETURNING FROM MY date with Teresa. I walked with my head high, listening with pleasure to the sound of my steps echoing off the pavement. “Teresa, Teresa,” sang my youth. Barely four days had passed from our first meeting and I was already riding the high crest of my love. With the submissiveness of a weak character – which I’d been told I had – I allowed Teresa to take over all my thoughts and imagination. Even when I was thinking about other things somewhere through the back of my mind’s eye passed the images of her face, her smile, her eyelashes with snowflakes on them or her hands in old leather gloves, which had became a holy relic to me.

We saw each other every day. We both had no doubt it was love. “Love, love,” I kept saying to myself aloud when alone in my flat. I hadn’t neglected the corpse. Fortunately the cold weather held fast so the regularly replenished ice kept the body from decomposing. Only once during the last three days had I wrapped some innards up in paper and discarded them on the suburban rubbish dump often visited by ravens and cats. That trip cost me a lot of time and effort and the result was rather measly. Once more I had to admit that the corpse was a tough opponent and fighting it required a lot of willpower, courage and ingenuity. I hadn’t given it much time lately but I wanted to bring it to an end as soon as possible. I was getting bored with it.

I was slowly coming to the conclusion that the period when the struggle with the corpse filled the void in my life was over. The corpse had been replaced by Teresa. Yet I could not accept this conclusion without reservations. I knew that a woman could not fulfill or replace all the various longings and desires that tore at my soul; I knew that nurturing my love for Teresa would mean killing it, too. And yet, under the influence of this girl I was beginning to recover my faith in life. I knew it was an illusion, and I kept telling myself so. I had wasted too many years dreaming about traveling, adventures and the exciting life that awaited me. (Too many times I had been punished for my dreams by everyday objects in our flat, by the lecture hall, by all that machinery of terror that closed up on me, seemingly forever.) Yet when I was with Teresa I felt calm and believed, against all reason, that I was still destined for great things.

These fanciful musings seemed to be confirmed by my recent experiences. After all, killing Auntie and struggling with the corpse was definitely something. And my situation as a man standing between th

e gallows and an unknown adventure was not devoid of a certain dramatic grandeur. Nevertheless, it’s not exactly the kind of drama I had in mind, not the sort of deed that Teresa’s knight should be famous for. Such and similar thoughts crossed my mind in those days. Those thoughts and reflections were rather superfluous, unable to affect the great lightness that filled me. The pangs of fear still happened. I was aware that I was pushing my luck, dragging my feet about reporting to the police while doing nothing about getting rid of the remains.

In such moments my head would explode with brilliant ideas of annihilating the corpse. Once, as I was falling asleep with the image of Teresa under my eyelids, I was gripped by a spasm of fear. Any attempt to talk myself out of it and stay in bed were in vain. I dragged myself out from between the sheets and went into the kitchen. I rummaged through the sideboard and found the meat grinder. With some difficulty I clamped it to the edge of the table, picked out a few chunks of dead meat and began to mince. My plan was terrifyingly simple, with the simple ingenuity of a perpetuum mobile. I would mix the minced meat with the ash from the stove in the bucket and then take it out as usual in the morning and dump it in the rubbish bin. As I earnestly turned the crank the work brought me peace, as it usually did. I thought of Teresa. Of our walks in the spring, which was just round the corner. Of alleys lined with young birch trees, of orchards, of those little white-and-yellow flowers which blossomed on the shrubs in spring. I was smiling and muttering to myself. Suddenly my bliss was shuttered by an excruciating pain. I had caught my finger in the meat grinder. I yanked my hand out and put it to my mouth, but dropped it immediately as the odor of the meat hit my nostrils. I picked up the crank again but without the previous enthusiasm. The work slowed. The grinder was getting jammed. I gave up. I was a picture of pathetic horror: standing in my pajamas working a bloody meat grinder in the cold kitchen in the middle of the night. Now my brilliant idea seemed idiotic. My mind drifted over to the question of how to disinfect the grinder. I threw the minced meat in the bucket and after some hesitation, the other two pieces, as well; after I stirred it all up, the ash covered the pieces so thoroughly they could not raise any suspicions. I went back to bed. The moment I closed my eyes the image of Teresa appeared before me to guide me into sleep.

I managed to get home just before the gates were locked. I was pleased I didn’t have to struggle with the massive rusty key. I ran up the steps and saw before my door two small human figures. Light shock gave place to amused annoyance. I recognized my granny and her daughter, Auntie’s sister. They both lived in a small town in the mountains, a good dozen miles away from the railway station. Auntie, and what she sent them, was their only livelihood. Granny, who was pushing eighty, suffered from chronic eye pain and smeared them with an iridescent white paste. It made her look like a strange bird. Seeing her, I always thought that if the biblical term “whitewashed tomb” actually existed, she would be it. Her daughter, a fifty-year-old virgin, was handicapped and wore very thick glasses, without which she was practically blind. Apart from that she suffered from a serious stomach disorder, and played the violin. I remember a visit we paid them a few years ago in their hometown. It was a warm September evening. A golden stream of sunshine flowed through an open window. It was a golden, lyrical moment. Aunt Emilia stood by the window, hidden from the courtyard behind the curtain, and played. I can’t remember the melody except that it was old and sad. When we entered the room she stopped and blushed like a schoolgirl. We had to plead with her for a long time to play something again. At long last, blushing and excusing herself, she agreed to repeat the concert. I remember vividly Granny’s face beaming with almost lewd pleasure as she listened to the tones of violin, and Auntie’s – approving but unemotional. I remember that I hated her then. Who knows, maybe here I’d be able to find the roots of my deed, if I could be bothered.

I sat the old ladies down and began to set the table. They both protested that they would not eat, even though they were hungry and watched my every move heralding the imminent appearance of food with growing excitement. It amused me. I put the kettle on and made a pile of sandwiches. I used up all the cheese, which was supposed to last me three days. I worked quickly and with confidence. A week of self-reliance had taught me a lot. I told the women that Auntie had left for a long business trip and tried to assuage their worries about the lack of letters and a money order. When supper was finally on the table, the women rose to say a prayer. I got up too. Until now on these occasions I always stood with my hands casually clasped behind my back and a blasé expression on my face. But the experience of the last few days cured me of my adolescent arrogance. I bowed my head lightly and clasped my hands in front of me. Toward the end I even made a vague gesture with my right hand. We sat down. The old girls ate with appetite. I excused myself and peeked into the bathroom. The corpse was well covered. When the ladies began to yawn I made a bed for them in the room, and for myself laid a mattress on the kitchen floor. It was hard and uncomfortable.

“Oyey! … Yey, yey!…” I heard Aunt Emilia screaming in the bathroom.

I jumped up and switched the light on. Groping my way through the hallway, I ran to see what happened. Aunt Emilia in her long nightdress was sitting in the bath with her feet high above her head. She was holding a lit candle in one hand while the other hand was making desperate waving movements.

“Who’s here?” she stammered when I appeared in the doorway.

“It’s me, Auntie,” I said as calmly as I could. “What happened?”

Aunt Emilia started gibbering again.

“There is someone lying here …”

I got scared. Aunt Emilia had discovered the corpse. She had to be killed. If I did it now, while she was still in the bath, I would spare myself the trouble of transporting her corpse. But then I’d have to kill Granny too. Three corpses on one head. No, that would be too much. I took Aunt Emilia’s hand and pulled her out of the bath.

“Someone’s lying there,” she was shaking with horror. “Jurek, dear, who’s there?”

Trying to calm her, I carefully examined the bath. The depression indicated the place where the stomach and the lower part of the body lay. I knew the arrangement of my corpse very well and could determine precisely the position of each body part under the sheet. Aunt Emilia had landed on the best-preserved part when she fell in. She had mistaken the bath for the loo. She was still very upset.

“Someone is lying there … I think … I felt it …” she kept repeating.

I took the candle out of her hand and bent over the bath.

“But Auntie,” I explained calmly, “it’s only linen. Look, there …” I carefully unfolded the sheet. I manipulated the candle in such a way so she could not see anything. Emilia was straining her sick eyes. She was calming down. Suddenly, when it seemed the danger was over, the light came on.

“Damn,” I cried out and raised my hand to my eyes as if blinded by the light. At the same time I pushed my elbow into her face, knocking off her glasses. “Oh, I’m so sorry!”

The bathroom was flooded with light now. Aunt Emilia stood by numbly, rubbing her face. She couldn’t see a thing. I took her gently by the arm and led her away to her bed. On our way we met Granny, who was awakened by the noise in the bathroom. She was wearing a white turban.

I fell into a heavy uncomfortable sleep, from which I soon awoke. Only now it struck me how much I’d grown used to sharing my loneliness with the corpse. The nocturnal presence of two old women in the house irritated and distracted me. I couldn’t go back to sleep. In the surrounding silence I picked out the slightest noise, barely audible squeaks of the furniture, the hollow, intermittent song of the kitchen tap. As my ears tuned in to those susurrations I could clearly distinguish the breathing of two sleeping women despite being separated from them by two closed doors and a hallway. Then the breathing stopped and changed into whispers. I couldn’t hear the words but the conversation grew louder, the beds squeaked and the room filled with a gentle bustle.

<

br /> After a few moments I heard the clanking of plates and cutlery. At first weak and timid, the clanking soon intensified until it sounded as if a noisy feast was under way in my room. Only the dinner conversation was missing. There were still some leftovers from supper on the table in the dining room and the old girls were apparently clearing them off. When the bustle died out I heard the women tiptoeing toward the kitchen. As carefully as I could I rearranged myself on the mattress. I wanted to be able to observe them without arousing their suspicion. The women slipped into the kitchen and slowly approached my bed. Granny stretched out her hand and scratched me lightly on my nose, I didn’t move. Then she whispered:

“He’s sleeping, good boy …”

“God bless him …” said Aunt Emily.

Assured, they turned away. The older led the younger, who in the dark probably couldn’t see anything. They were heading for the sideboard but bumped into the low, broad kitchen table on which I had left a bit of bread and sausage. They bent over the table and searched it thoroughly the way one looks for a lost ring in a meadow. They didn’t reach for a bigger piece farther away until they’d cleaned up all the crumbs before them. When the table was clean they moved on to the sideboard. The kitchen resounded with the music of feasting again. I knew that in the sideboard there was only a jar of marmalade, some sugar and a small bag of flour. The ladies consumed it all eagerly. Granny made little cakes of flour and marmalade, sprinkled them generously with sugar and fed them to her daughter. Herself, she ate them without sugar, protesting she didn’t like them too sweet. When they got to the larder they were met with disappointment. The door was locked, the key hidden in an unknown place. I would have gladly gotten up and treated the old girls to all the food I had but was worried that catching them out on their greedy raid would embarrass them. So they stood hopelessly before the door examining the empty keyhole. Aunt Emilia threw in the towel first:

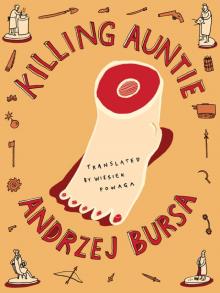

Killing Auntie

Killing Auntie