- Home

- Andrzej Bursa

Killing Auntie Page 8

Killing Auntie Read online

Page 8

“It’s too risky, darling. It’s my problem.”

“I thought you’ve understood by now that problems aren’t ‘yours’ or ‘mine’ – only ‘ours,’” She answered contrarily. “And if not, too bad.”

“But Teresa, you know the situation, I’m not hiding anything from you. I simply don’t want us to go out on our first spring walk with such cumbersome baggage.”

“It would be more cumbersome and unpleasant if you were to do it on your own. Isn’t that so, my little one?”

“Yes, but do I have the right to put that burden on your shoulders?”

“It’s like our baby. A consequence of me being with you.”

On Sunday morning, some time after eleven, we got off a bus at the edge of a forest. Springtime and blue skies were all around us. The paths were dry but the fields shimmered under a spread of snow. We squinted our eyes against the sun.

“Isn’t that parcel too heavy for you, darling?” I asked.

“No, my little one, it’s not.”

“Come on, let me carry it for you.”

“Certainly not. You’re carrying the heavier one anyway.”

“That’s ok, you are a woman. I should carry you in my arms – not make you carry parcels.”

“The times we live in, eh?”

“You teaser, you,” I laughed and put my arm around Teresa. She looked into my face, her eyes burning with fire.

“Ah, my little one, I’m so happy.”

We put our parcels on the ground and began to kiss.

“Someone’s coming,” said Teresa suddenly. “Stop it.”

We saw a man approaching slowly from the fields, carrying a gun. We picked up our parcels and walked on. The official cap of the forester reminded me of things I would rather forget today. Teresa noticed the change in my face.

“Why so sad, my little one?”

“Oh, it’s nothing, nothing really,” I replied, and then added sternly. “Don’t look at the sun.”

“Because?”

“Because you will damage your eyes, madame.”

“What …? Ah, madame will damage her eyes … Oh, my little one …”

At the edge of the forest stood the yellow, ungainly building of the inn. We were the only customers there, except for a coachman in a padded work jacket drinking beer at the bar. Whenever I passed the inn before, the iron grille on its door was always shut. To this day it remains a mystery to me why it was open on that April Sunday. We sat down by the window, beyond which a panorama of the surrounding wooded hills spread out. We put our parcels on the empty chairs. After a while we were approached by a boy in a dirty apron and a face that was meant to show us we had disturbed his peace. After some protracted negotiations he agreed to bring us sausages and tea. We ate with an appetite of kids on a field trip, joking and laughing. When we finished our tea, we lit our cigarettes. The sky began to turn gray. Warmed and tired, we were looking at each other’s faces and hands, which reminded us of our pleasures. We knew it was a beautiful moment. The gray mist clinging to the treetops invited a mood of longing and dreaming. So I began:

“You may not know it, darling, but my father lives in Buenos Aires.”

“In Buenos Aires? And you never told me?”

“I’m telling you now. He lives in Buenos Aires and is a very rich man. The only problem is how to get there. Do you think it’s impossible?”

“I don’t know, love,” said Teresa softly, “but since I met you nothing is impossible for me. Before I met you I had never believed in any possibility of changing my fate. And to tell the truth, I never thought of it. But now, when I’m involved in such an extraordinary affair … It is extraordinary, isn’t it, love? But maybe I’m hurting you, talking about it?”

I didn’t reply. My eyes fixed on the horizon, I sat in silence, deeply moved and happy. Teresa’s father was a forester and she spent her childhood and teenage years among the woods and lakes. Her first steps were blessed by the purity of nature, just as mine were cursed by neurosis. My longing for the forests and animals, stifled by years of misery, and forgotten in the recent days of the struggle with the corpse, now began to stir inside me uncomfortably. Many times I tried to see it in the cold light of reason, that it was all a question of love, that I should focus on happiness, for Teresa loved me too. Indeed I had many moments of true happiness, yet I could not free my mind from anguish. And it wouldn’t be so bad if it weren’t for the matter of my corpse. I knew that by hiding my feelings from Teresa I was deceiving her, and it hurt me. I could try and summon all my strength and remove the rest of the remains. But I had no strength left. Teresa competed with the corpse, and won. Over the last few days I hadn’t undertaken any actions, only once slipping out at night with a small package wrapped in a newspaper and discarding the contents on a rubbish dump frequented by cats and crows. I felt burdened by the corpse like a man burdened with a family, of whose existence he doesn’t dare to tell his mistress, while his inherent decency prevents him from shedding the burden. Even in the happiest moments, when walking with Teresa through empty fields, joyful and lighthearted, bursting with insuppressible laughter, so inextricably connected with our love, I carried the thought in my mind, which would suddenly flash like a signal – the corpse.

After a while I continued without looking at Teresa:

“I know a sea captain in Szczecin. A good man. When I was a child he used to carry me in his arms. An old, trusted family friend. I’ve learned he works now on a regular line to South America. Will you come with me?”

“Ah, Jerzy …” Teresa stroked my hands with her fingertips.

Quietly, in low voices, we began to plot our escape. We refrained from showing any excitement in anticipation of all the exotic places we were going to see. No feverish discussions, no falling for the thrill of planning. We spoke in a calm, factual manner. I deliberately pointed out the difficulties piling up before us, while slyly slipping in suggestions of how to overcome them. Teresa pondered them, knitting her brow, returning her opinion in slow, measured words. When at last we reached a contented silence, she said:

“Sometimes, when you are not with me, I feel you do not exist at all. I’m sure that in a few hours I’ll think this conversation is a dream. And yet you are real. I’m touching your skin and hair. My boy, my lover. You’ve put too much meaning into my life. Sometimes I feel it overwhelms me. But I know you cannot be any other way. I don’t think I would love you otherwise, if you weren’t full of all those mysteries I still know nothing about.”

I squeezed Teresa’s hand. She cheered me up. I felt like a good man. I gave a girl more than she expected. I made her happy the way I once made that old Capuchin priest in an empty church happy.

“Do you want to be with me?” I asked.

“I do.”

We threw the parcels into the river from a high, overgrown bank. We didn’t discuss their contents. Only on our way back through the woods did Teresa ask me, a little concerned:

“Darling, what was in my parcel?”

“Well, you know, surely …”

“Yes, but … which part?”

I remained silent.

“Come on, tell me. The leg?”

“Of course not, the leg would have been much heavier.”

“I don’t mean the whole leg …”

“Teresa, stop it.”

“You’re right. I’m sorry.”

She quickly lifted my hand to her lips. We sat down on a stack of logs in a clearing. Teresa took out two rolls and offered me one. Leaning on a log, I was contemplating the clouds drifting over the treetops.

“You know what, Elfie?”

“What, love?”

“Tomorrow I have national defense training again.”

“Poor thing, I’m scared.”

“Why?”

“I’m always scared before your training.”

“Don’t worry. It won’t be for much longer now.”

“What makes you think it won’t be for much longer

?”

“I’m sure of it, my little one. Before I met you, I didn’t believe my life could change in any way. And I accepted that. In fact, it never bothered me much. But now, when I’m involved in such an extraordinary affair … Just think, Jerzy, it’s amazing …” She fell silent and, after thinking for a while, she added with conviction: “I just know that everything will turn out as you want.”

I waved my hand wearily. I knew that Teresa didn’t really understand any of it. But her optimism and unbounded faith in me began to disturb me. When we plotted our escape, planned our travels and other adventures, I usually put forward the most bizarre, fantastic ideas. I could even find logical arguments for them. And the down-to-earth, practical Teresa fell for my fanciful nonsense. As long as we believed in it together, it was all very nice. But now I was struck by what an enormous distance separated me from those moments. Did it mean I was bored with love? Probably not. I needed Teresa, I wouldn’t want to lose her. Yet I realized with absolute clarity that the only real thing was the corpse, at once a millstone around my neck and my lifeline.

11

I CHECKED THE TIMETABLE AND REALIZED THE BETTER OPTION would be to return by bus. Any other time I would have been disappointed, but today the prospect almost pleased me. I was disappointed by The Other Town. I tried to shorten the wait for the departure by discovering something special about buses. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find anything special. Their shape and yellow headlamps just didn’t fit into any metaphor. They were horrifying. But only in their objective existence. I turned my eyes to the station clock, hoping this poetic object might retain something of the fairy tale I’d expected from The Other Town. I looked at it intensely, lingering on the bright little star at the top. Still, I felt I was losing my focus despite putting all my imagination and intelligence into the effort. Suddenly I heard the characteristic blare of a horn and at the same time, maybe just a few seconds before, a young voice:

“Careful, mister!”

Someone yanked my arm. I let myself be pulled back. A few inches before my eyes passed a bus. I turned around towards my rescuer and recognized The Girl I Used to See. Before I could get my bearings and get out of harm’s way, I stood in the middle of the road used by buses returning to the terminal. I had already grasped the meaning of this laconic message. Not for the first time The Girl interrupted my most carefully laid plans of suicide, which returned later only with double force.

I took my seat by the window and tried to adopt a position that would allow me to spend the long journey in the best possible comfort. I focused my mind on that. As the driver switched the engine on, someone sat next to me. I turned my head automatically. It was The Girl I Used to See. I shuddered. I turned my head away and fixed my eyes on the window. This situation required some reaction on my part. I was trying to persuade myself that fate had graciously given me a chance. But then, I knew I couldn’t take it, and felt rather ungrateful towards my fate. In the end I reached a compromise that best suited my mixed feelings: by observing The Girl I would destroy the myth of her Otherness, which in the meantime I had cultivated in my mind. Until now, almost always, I had seen her from a distance. Now that my face was practically next to hers, I would discover how common she really was.

I observed The Girl closely. Pretending to stare absentmindedly through the window, I studied her reflection in the windowpane, her profile, her hands; I looked for signs of weariness in her face, which would make her just like the other passengers. After a while I could conclude with satisfaction that The Girl was tired; she even yawned once. And yet I felt defeated. The Girl still managed to retain the mystery of previous encounters. The distance I felt then did not diminish now, when our shoulders pressed against each other in the shared misery of fellow passengers. Her remoteness could be punctured only by talking to her directly. At first I thought of starting a casual conversation, in the course of which I would defeat her apparent unavailability. Except I wasn’t really sure that victory would be mine. After all, talking to strangers had never been my forte. I cursed the situation forcing me into this. At that moment it was no longer just a question of destroying her myth but of wasting the chance – the chance I had already forfeited. I was not afraid of embarrassment. I was simply too lazy to undertake such a great effort. The thought of having an empty flat at my disposal disarmed me completely. And yet I was not ready to surrender. I could only console myself that in a couple of hours we would reach Our Town and The Girl would disappear around some street corner. That thought actually hurt. I counted the short stops bringing that moment inexorably closer. Suddenly I hear a loud crash and the bus ground to a halt.

The driver jumped out of his cabin and shouted something after a short while. Slowly, people started to leave the bus. I got moving too. The driver and the conductor were walking around the bus with their flashlights. It looked like something serious. Passengers complained and murmured among themselves. They looked like a lost herd of sheep; the sight cheered me up a little. We all stood by the roadside, close to the bus. Almost all the men lit cigarettes. I looked around thoughtlessly and suddenly saw a slender figure marching down the road with light, confident strides. It took me awhile to realize it was her. The Girl’s movements were so strikingly different than the rest of the passengers, showing no sign of nervous impatience about the delay. It was hard to believe she belonged to the mass of commuters shuttling between the towns. The moon had just lit the road; there was no danger of me losing sight of her again. Some people began to walk around in small circles, as if locked in an invisible cage. Others took advantage of the bushes on both sides of the road.

I joined the walkers for a while and then broke away to follow The Girl. We left the bus far behind. The Girl marched on, her pace steady and purposeful, as if she knew exactly where she was going. We passed a wooden building, then a birch tree. The road began to rise. I expected that once The Girl reached the top of the hill she would turn around and start coming down. I stepped out of the shaft of light and over to the side. But she marched on. For a moment I lost sight of her. I hurried up a little. I was beginning to enjoy this. Suddenly I heard a roar. Its muffled sound confirmed we had covered quite a distance. Then another roar. After a while I heard the quiet purr of an engine. The Girl stopped and spread out her arms undecidedly. For a few seconds she stood still, as if struck by the moonlight. Then, slowly, she lowered her arms and just as undecidedly turned around. At first she walked slowly, like someone out for a stroll, then she broke into a run. I stepped out of the dark and walked toward her. As she passed me by I said:

“The bus is gone.”

She stopped dead in her tracks. She looked at me carefully, without fear, and asked sharply:

“Who are you?”

“Ah … Mm…” I stammered. At first I wanted to say, “A murderer,” for at that moment that was the most important thing about me. But I bit my tongue.

“A passenger,” I said at last.

We began to walk slowly, following the direction in which our bus disappeared. We walked, picking up the pace, without looking at each other. The icy winter road, carrying us forward like a conveyor belt, the white downy fields, clusters of houses and lonely trees marked the rhythm of our march. The moonlight shone all the time. Now and again a hare skipped across the road. I was getting tired. The march, at first a relief from the murderous seat on the bus, was now beginning to turn into another type of torture. A slight nagging discomfort in my shoes and clothes grew sharper and more painful with every step. My feet began to slip. I stole a glance at my companion, wondering if she too had reached the point of exhaustion. But The Girl’s clear face seemed just as untroubled as it was on the bus. I had no idea how far Our Town was, or whether it was at all possible to get there on foot. Several times I wanted to ask The Girl but I couldn’t bring myself to do it, fearing that such questions were ridiculous in light of the merciless pace of our march, the road, the moonlight and the monotony of the landscape. When we passed the fourth village t

he road turned into the woods.

A grove of tall pines was quickly getting thicker, with more firs and naked deciduous trees. The moonlight began to disappear. I felt for The Girl’s hand but found only the off-putting coarse sleeve of her coat and quickly withdrew my hand. Suddenly The Girl turned and, jumping over a ditch, stood on a high path wending among the firs. With some hesitation I followed. Seeing me undecided, The Girl beckoned and said:

“Come.”

Or maybe she didn’t say anything? We followed a slippery path, full of craters and roots. I watched my step but at some point I lost my balance and fell. The Girl stopped abruptly and when I quickly picked myself up, we moved on. At last we came to a small dell, all silvered and sheltered on all sides. The Girl turned to me and said:

“We’ll rest here.”

I didn’t quite know how to behave in this situation. I looked around the dell and hesitantly fingered my coat buttons, wondering if I should take it off and spread it out somewhere on the snow. But The Girl started rummaging around in the low firs. Bent low, she swiftly ferretted under the brush like a small tornado. After a while she returned with an armful of branches.

“Help me,” she said. “Here, hold this. Here …”

Obediently I took hold of two sharp branches.

“Now here,” ordered The Girl. “Good.”

Soon I was working like a well-trained assistant, eagerly passing the prickly branches from hand to hand. The Girl did not slow down. She no longer spoke to me, only praised my diligence or criticized my sluggishness with an eyebrow or a grimace. Before long we had a thick mat. I don’t know how long it took us to build our fir hut; at any rate I had to admit it was very warm and comfortable. Half-lying on the hard fir mattresses, we warmed up by the fire in the center of our camp. I raised my collar and stuck my hands inside my sleeves, worried that the warmth of the fire would prove illusory and the cold would start to bite. It was unnecessary. Our little house was getting warmer and warmer. Soon I was sweating like on a hot July day. Above the trees blew a sudden gust of wind. I could see thick trunks swaying a few feet away from our fire but here it was warm like in an overheated room.

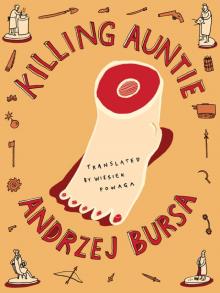

Killing Auntie

Killing Auntie