- Home

- Andrzej Bursa

Killing Auntie Page 9

Killing Auntie Read online

Page 9

The Girl took her coat off and her head scarf, yawned and began unlacing her boots. She got up and slipped them off without using her hands. I was surprised to notice that our hut, though very cozy, was nevertheless high enough for a grown woman to stand comfortably inside it. The Girl took off her trousers and sweater and lay down, wrapping herself in her coat. I looked at her in silence, swaddled in my winter coat with my raised collar and the lowered earflaps of my ski cap. The Girl wriggled for a while on her bed, then got up and moved closer. She took my face in her hands and suddenly kissed me on the mouth.

I stretched my arms out and embraced her. She started to pull away, laughing in a metallic, sinister way. Entangled in my coat, I couldn’t decide if I should take off my gloves or my helmet-like hat, or hold tight to the trophy that was slipping out of my hands. The Girl helped me. She sat close to me and soothingly stroked my face and my hands. She took my gloves off and cradled the palm of my hand to her cheek. Then she let it slide off her knees, without letting it go. She brought her face close to mine and asked:

“Are you brave?”

“I am,” I answered with conviction.

The Girl slowly raised my hand to her mouth and suddenly bit it. I grit my teeth. She held the bite with increasing force. I put my other arm around The Girl and started playing with her hair to divert my attention from the pain. She didn’t react. At last she let go. I raised my wet, teeth-marked hand to my eyes. The Girl jumped up and fell onto her bed, wrapping herself tightly in her coat.

“Watch the fire,” she called out, turned her back and almost instantly fell asleep.

I was hit by a wave of weariness too. With great effort I pulled up the sleeve of my coat to check the time. It was three in the morning. I thought of fighting sleep with a cigarette but the matches were wet and I had no strength to move closer to the fire. I just fixed my eyes on it with a firm resolve to stick it out like this till dawn. But The Girl’s presence bothered me. I stretched my hand out and felt for her. I found a soft tress of hair and a cold smooth forehead. The Girl twitched and turned around. I felt embarrassed. Our agreement was that I was supposed to watch the fire. I turned my eyes back to the fire with renewed zeal. Another gale swept over the trees. Our little hut was getting warmer. I was boiling. Once more I tried to unbutton my coat but then gave up, suddenly worried I might catch a cold. I raised myself a little and immediately crumpled like a rag doll. My eyes shut automatically, against my will.

In the morning I was woken up by the intense cold, as if I had slept outside all night. I leaped to my feet. The Girl, dressed and ready to go, was smothering the fire with snow. All around us were scattered small, broken branches: the remnants, I suspected, of our little hut. I stood forlorn and cold. I felt ashamed, before the Girl, of my helplessness and lack of discipline in watching the fire. I didn’t look great, I knew that. Without paying any attention to me, The Girl was trampling over the fire; then she bent down and threw handfuls of snow in my face.

“Catch me!” she cried cheerfully and ran off.

I started after her in hot pursuit. We ran among the trees, knocking pillows of snow from the branches, and then ran down the road. At last The Girl stopped, looked at me, and burst out laughing.

“You fell asleep last night. The fire would have gone out if I hadn’t woken up in time,” she said. “But it’s OK.”

The last sentence she pronounced softly but firmly. I stretched out my arm automatically. She took my hand and pulled me after her. We walked fast through a silent misty wood.

“There is no point in looking for a bus,” said The Girl. “My house is not far from here. I live outside the city. We’ll go to my place and have a cup of tea. We should be there in an hour.”

The wood began to grow thinner until it thinned out into groves, which I remembered from my own walks. Then on the horizon loomed the panorama of Our Town; we came out into an open space. Having passed a dirty village with huddled houses, still asleep, we turned onto a side road and after a while stopped before a big rusty gate. The Girl unhooked the chain and we entered a wildly overgrown, neglected park. Next to the gate, among the trees, stood a long yellow building, which looked like a warehouse or a coach house, but was empty. Farther on, along the alley, we came to some concrete foundations and empty swimming pools. Then again thick shrubs, almost completely covering the narrow path under our feet. Finally, we stopped before a barricade of empty, rusting cages. The heap of scrap was interlaced with tree branches; in the summer it must have created an impenetrable, iron-green fortification. The Girl pulled me again and we went inside a huge concrete tunnel, about six feet high.

After a few echoing steps we came out on the other side of the barricade. From the back it didn’t look so fierce. Straight away my eye spied in the heap of creaky old iron a few weak spots through which one could easily sneak back onto the other side. We walked on among empty pens, cages and concrete ditches. When we passed a low hedge it was clear we were in a zoo. At first glance it didn’t look much different from the junkyard we’d just passed. The animals sat inside their boxes, the floors of their cages covered with piles of snow. Only an old vulture flapped his wings in the nearest cage, and the black silhouette of a doe hovered above an iron fence. I remembered that I had once been in a zoo at this hour and wanted to tell The Girl, but as soon as I opened my mouth she shook her head sternly and silenced me. She took me by the hand and whispered into my ear:

“Come. I’ll show you something.”

I nodded, obediently refraining from saying anything. The Girl slowed down. We walked carefully and in silence; only her grip on my hand grew stronger. I couldn’t understand why we were creeping like this, for that was the only way I could describe it, but I crept as best I could, holding my breath and trying to take steps without making any sound. When we got to a big hut, The Girl motioned me to hide behind a tree trunk. Leaning out from behind the tree, our faces were practically touching the wire fence of the cage.

Inside the cage, which was as huge as an auditorium, on a concrete shelf built into a massive rock, two lynxes were copulating. They did it softly, gracefully, soundlessly, without purring. It went on for an embarrassingly long time, and in silence. It began to get on my nerves. I felt I could not articulate any kind of reaction to this phenomenon, fundamentally indifferent to me and outside my direct sensual experience yet totally absorbing. I looked at The Girl. Her face was calm and beautiful as usual. She was watching it with concentration, her forehead slightly furrowed. Her lips were gently pursed in a kind of smirk, neither contemptuous nor ironic. The aroused animals began to moan and purr. It was unbearable. I tried to wrench myself free and cover my eyes with my hand. But The Girl would not let go, her grip growing stronger still, her fingernails sinking into my hand. It was only thanks to my thick gloves that she didn’t draw blood.

“Let go,” I hissed with my throat tight. “Let go, now! I’ve had enough. This is ridiculous …”

I was flailing madly behind the tree, unable to pull free. After a while I realized The Girl was no longer holding my hand; I was simply rooted to the spot. The lynxes’ moans were growing louder and louder, reaching the pitch of beastly whining. I leaned against the other side of the trunk and with my eyes shut, waited out the feline orgasm. After another minute I decided to open my eyes. I was struck by the stillness of the surrounding. My writhing and flailing of a few moments ago seemed utterly out of place now as I stood in the midst of a silent snowy landscape. The lynxes lay on their bellies scratching each other lazily. The female lay with her hind legs stretched out like a woman’s. A bird swayed a branch above my head and a single black leaf fell on the ground nearby. I turned around looking for The Girl but she wasn’t there. I wanted to call her but remembered that I didn’t even know her name. I walked around the cage, checking behind other trees; The Girl was gone. I became angry: What would be the point of looking for her anyway?

I checked the time. Ten o’clock. I decided to take the shortest route back

to town. But as soon as I turned toward the alley I saw her, waiting for me.

12

THE FOLLOWING MORNING BEFORE DAWN I THREW MY SKIS over my shoulder and headed for the zoo. In fact, I hadn’t arranged to meet The Girl but I was hurrying as if late for a date. The workers, gathered in groups at the bus stop, looked at me gravely, even hard-heartedly. I didn’t have the time, or the patience, to explain to them that my needs, forcing me to take a ride to the woods at this time of day, were just as unforgiving as theirs, forcing them to hurry to the cigarette factory. After passing the bus stop I fastened the skis on and set off across the empty fields.

The gray skies made the snow glisten with a turbid sheen, which was hard on the eyes. The first part of the run, passing houses and cowsheds, was unpleasant, in fact, and now and again I asked myself if I shouldn’t go back. How would I justify to The Girl such an early visit? Once inside the forest I began to enjoy the run, and the freedom. Sliding along the downy paths, past the black tangled mass of shrubs and bushes, here and there I would knock off a thick snowy hat from a fir branch, crying out in hushed excitement as I went along. I didn’t let myself get carried away, constantly reminding myself I had to make it on time for the feline heat.

I entered the zoo through the main gate. I expected The Girl to be waiting for me there and was rather disappointed when she wasn’t. I walked slowly along the alley. The animals watched me without any fear in their eyes. The bears stood up on their hind paws and had a closer look at me, but didn’t turn their heads when I disappeared from their sight. A young lion ran away at first and then stopped with his paw in midair, above a still quivering wooden ball. I turned back and started toward the mouflon pen, behind which stood the caretaker’s black hut. The hut looked as if someone had shoveled the snow in front of the gate, locked the door, bolted the shutters and left for somewhere far away. I stood before it for a long while, hesitating whether I should knock on the shutters or not, but in the end I lacked the courage. I turned back onto the main alley and began to move towards the other entrance, the one we had used. But I couldn’t find the way. I had no idea which end of the park the lynx cage was at, which could serve as my orientation point.

Sliding along on my skis, I came across a long wooden building. Because I was feeling a bit cold, I unfastened the skis and went in through the half-open door. The inside of the building was like an elongated, over-wide corridor. Along the walls were cages with small parrots, hummingbirds and white-footed voles. The stench was overpowering. I lit a cigarette and moved towards the other end of the corridor, where I saw an open window. It didn’t, as I expected, open up to the outside, but looked into a small room with a floor covered by layers of cotton wool and a small barred window that was closed. A big monkey in a black waistcoat sat in the middle of the floor. The animal held some kind of a magazine and was leafing through it with great concentration. After a while the monkey put away the magazine and pulled a sheaf of loose pages from his waistcoat pocket. I managed to catch a glance at the magazine’s cover; it was an old satirical German weekly.

Meanwhile the monkey spread the pieces of paper out on the straw floor like someone dealing a game of Patience, except that the cards were uniformly blank. He fiddled with the glasses on his nose, though in fact there was just a wire frame without lenses, and sank into thought over his cards, as if trying to decide which to choose. Then, with a quick, thieving swipe, he snatched one of them from the middle row, moved to the window and raised it up to the light. As far as I could tell from that distance, the watermark on the paper was an erotic picture, drawn in a vulgar and naturalistic way. The monkey examined the paper at length, nodding his head with appreciation, then picked out another one and again looked at it for a long while. By the third card, the monkey’s breast heaved with a soft sigh. He glanced at the fourth card quickly, as if not interested, and immediately reached greedily for the next. I had had enough.

I stamped my foot loudly and cried: “Shoo!” The monkey froze with a card in his hand, turning his eyes on me with a tense, painful look. Suddenly he leaped in the air, jumped on a ledge above the window and a metal curtain fell right in front of my nose. I began pummeling it, without thinking. Inside the room it was totally silent. From without, the parrots raised a deafening racket, their cries piercing my ears like steel shrapnel. The baboons and chimpanzees began thrashing about in their cages.

Tormented, I ran out of the building, slamming the door behind me. My skis were waiting for me in the snow, familiar and friendly. I fastened them on and threw myself into a run across the park. Suddenly, as I reached the main alley, the silence was rent by a hoarse, guttural shriek. I recognized the lynxes’ call of love. Automatically, I turned in that direction. The noises grew more frequent; the intercourse must have been reaching the climax. I ran as fast as I could. At last, in the perspective of empty pens and barred enclosures, I saw the lynx cage. The Girl stood outside the caretaker’s hut, pale, with eyes shut. Her face was somber, pained. I ran up to her and grabbed her in my arms. We fell on the snow. The Girl was kissing me feverishly and passionately, not possessively as before, but submissively, like a woman. The skis, still fastened to my feet, splayed widely, drawing long tangled spirals on the snow.

When we got up The Girl immediately returned to her previous role. She helped me wipe off the snow and in a dry, matter-of-fact tone, she observed that I was cold, and thus she invited me in for a cup tea. The caretaker’s house was not abandoned, as I thought. We sat on the edge of a plush, richly tasseled sofa and drank our tea in silence. Apart from the sofa the room didn’t contain any other furniture. The kitchen, however, was crammed with chairs, a long ungainly table and a sideboard.

“My father,” said The Girl, “is of the opinion that I can receive guests only when the room is fully furnished. That is, when it has a table, armchairs, a linen cupboard and a clock. He thinks that now it would be improper to bring people in here. But I love you.”

The Girl slurped her tea and we fell back into silence. I looked around the room and suddenly noticed a white piece of paper lying on the shiny floor, the same kind of paper the monkey had been looking at. I decided not to pay it any attention, but the paper seemed to fill the whole room and draw my eyes with magnetic force. I was trying to concentrate on her profile and her hands but my eyes, even when wholly focused on her figure, slipped down onto the floor and secretly sought out the accursed piece of paper. The Girl sat slumped, saying nothing and sipping her tea, of which she seemed to have prepared copious quantities for the two of us. I turned my eyes to the window but somehow the card still remained within my field of vision. The Girl lightly took my hand. I reciprocated with a gentle, though rather mechanical, squeeze. The presence of that card embarrassed me.

“Let’s kiss,” offered The Girl.

We began to kiss, but we were not enjoying it. Our kisses were cold and clumsy. I realized that The Girl simply had no idea how to kiss, as if she had never kissed in her life. We lay next to each other.

“We love each other,” said The Girl indifferently.

“I love you and you love me,” I confirmed, kissing her gently on the cheek. I fell into musing about our few common experiences. I told her about our little fir hut deep in the forest. The Girl listened quietly and when I fell silent she said:

“We built the little fir hut in five minutes. It’s all nonsense. The little hut you were talking about is impossible, isn’t it. My big, silly boy. You believed in a fir hut …”

I wanted to protest but she calmed me down with a touch. The sound of a bell came from behind the window; with it came the sound of animals from all corners of the zoo. The Girl jumped off the sofa.

“Father is about to start feeding the animals. Come with me, you have to see this.”

The Girl bent down and picked up the white card from the floor. She crumpled it quickly in her hand, then tore it into little shreds and threw it into the kitchen.

“I’ve had enough of this filth,” she sigh

ed. The bell whose ring had gotten us out of the empty room was affixed to the shaft of a cart, which was drawn by a donkey. A small man wrapped in a long black sheepskin and a big hat walked alongside the cart.

“We have a guest today,” called The Girl. “I wanted to show him the feeding. You will start with the predators, won’t you? Great. I knew the predators would be first.”

The father didn’t answer but The Girl kept talking, answering her own questions, laughing and teasing. The father stopped the cart in front of the low long shed and took out a basket filled with chopped-up meat and bones. His face was so swaddled in the collar, scarf and hat that I could not make out his features. They didn’t seem to be that interesting anyway; his face was flat and unshaven. The father went back once more and brought out a second load of meat. When he came out for the third time he was carrying my auntie’s corpse. From the first glance I had no doubt it was the very same corpse. Its limbs were cut off by the knees and elbows, the head chopped off with an axe. Father put the naked corpse on the cart and we moved on. The Girl squeezed my hand and whispered into my ear:

“We’ll be feeding our cats, you know. Our wonderful lynxes.”

I nodded my head and lightly brushed her head with my lips. We toured the whole zoo, stopping in front of the predators’ cages. All that time I’d observed the naked torso trembling on the cart, making sure it indeed belonged to my murdered auntie. There seemed to be no doubt. The torso bore all the familiar marks: the signs of my victories and defeats, and on its side I even recognized the bite marks from Aunt Emilia and Granny. At last we got rid of all of the feed except for the corpse, which remained alone in the cart.

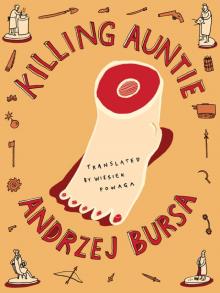

Killing Auntie

Killing Auntie